Ironworker Outreach

Ironwork is primarily about building things: raising steel structures, working rebar to reinforce concrete, adding finer touches of ornamental metal—all of the work that lifts buildings and other structures up. (Then the rest of the trades come along and add to what we built.) It’s relatively straightforward. But building and maintaining an Ironworkers union, well, that’s not nearly as straightforward. Adding apprentices, bringing in new journeymen, maintaining standards—all of those things are necessary to have a strong union. And a big part of that is outreach.

What is Outreach?

It’s recruiting new apprentices, basically. Trying to let people know about ironwork as a career, and the impact it can have on a person’s life. Sometimes it’s just planting the seed in a high school student’s head; other times it’s showing someone who needs a new career that ironwork might be for them.

Who Do Ironworkers Reach Out To?

In a word, everyone. We’ve mentioned before that the Ironworkers Local #512 welcomes people from all walks of life. Our ideal Ironworker candidate is someone in their mid-20s who has tried a different profession or college and found it wasn’t a good fit. People in that situation typically have a keen interest in the benefits the Ironworkers’ Union has to offer; many of them have the kind of everyday responsibilities, like a spouse, child, mortgage, etc., that help motivate them to go to work every day. But it is very hard to find a place that gathers people with those specific circumstances in one place. So, we reach out to schools.

We hold more than 50 outreach events across all three of our regions each year, and most of that involves high schools or trade schools. College welding programs, in particular, are a good place to find future Ironworkers. They usually are full of people who like working with their hands, building things, and are often looking for alternatives to what can be pretty boring factory work.

Why Reach Out?

New Ironworker apprentices are the fresh blood of the union. They come in, start their “earn while you learn” apprenticeship, and they see the benefits in their bank accounts right away. On a jobsite, it also quickly becomes clear that by becoming a journeyman Ironworker they can build a long, successful career and enjoy a dignified retirement. But what isn’t as obvious is that their earnings also help support the Ironworker’s Union as a whole, which means helping to pay for retirement and health care for their older brothers and sisters, exactly the way those older brothers and sisters helped grow and support the union’s membership when they were apprentices. Ironworkers call each other “brother” and “sister” because the relationships are, in fact, almost familial (sometimes they literally are; ironwork seems to be passed from parent to child like brown hair or blue eyes). But we need new apprentices to keep the work going and the union thriving. That’s why we spend so much effort on outreach.

Ironworker Outreach Events

Our outreach events are kind of like job fairs, but centered on the construction trades. There will typically be representatives from the Ironworkers, of course, but also several other unions: carpenters, laborers, electricians, boilermakers, bricklayers, masons, and many more. These different apprenticeship programs will gather at some central location, like a high school. But it can also be a larger venue, such as Grand Casino in Hinckley, Canterbury Downs in Shakopee, the Rochester Convention Center, AMSOIL Arena in Duluth, the Boy Scouts Center at Fort Snelling, North Dakota State University’s Fargodome, and more. Students are bussed to these events, and we all pitch them on the benefits of a career in the building trades. Sometimes we talk to 1,500 students in a day at these events.

Another way the Ironworkers do outreach is to host students from area high schools and other community groups at any of our three of our training centers in St. Paul, MN, Hermantown, MN, and Bismarck, ND. These groups spend anywhere from a couple of hours to a few days learning what Ironworkers do, seeing some of the work, and getting a sense of what ironwork is like from Ironworkers themselves. These events are generally our most effective: people who are interested in ironwork can get hands-on experience and really get a feel for whether they think they’d like ironwork.

No matter how an Ironworker finds their way to Ironworkers Local #512, they quickly find they are part of a hard-working community that supports and lifts each other up. And that might be just as much of an appeal as the good wages, benefits, and retirement. (But those help a lot, too.)

Welding Continuity Logs

We’ve written about welding as part of Ironwork in the past. Learning to weld is a standard part of Ironworker training in our apprenticeship program. Ironworkers obtain certifications for various types of welding. After they earn those certifications, they have to maintain those skills by welding in those processes at least once every six months. Those instances of welding in the certified processes are tracked in what’s called a welder’s continuity log.

American Welding Society Requirements

The reason for this is very simple: what you don’t use, you lose. And that’s definitely the case for welding. The American Welding Society (AWS) establishes the standards for welding in the United States. These standards are set according to the rules of the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). The AWS code book Specification for Welding Procedure and Performance Qualification says, “When he or she has not welded with a process during a period exceeding 6 months, his or her qualifications for the process shall expire.” Maintaining the continuity log means a welder can document that they have welded in a specific process for each 6-month period. If the log is kept up properly, the welder’s certification could go on indefinitely. All of this is to ensure that Ironworkers stay current on their skills and are performing the work correctly and safely.

Staying Certified

This requirement covers all welding processes, which is a long list of acronyms, only a few of which are generally relevant for Ironworkers. Our focus is on SMAW (shielded metal arc welding) and FCAW (flux cored arc welding), with GTAW (gas tungsten arc welding) and GMAW (gas metal arc welding) coming in a distant third and fourth. Within the identified processes, there are hundreds of individual certifications a welder can obtain. Some of them get a little redundant or are superseded by other certifications. A recent Ironworker Local #512 Apprentice graduated from the program with 15 certifications; that’s the most we know of held by an Ironworker.

If an Ironworker goes six months without welding in a certain process or certification, their certification expires. Recertification takes time and money. A typical recertification test costs about $50 in plates and filler metal. Then there’s the time required, about 6 hours, for the Certified Welding Inspector (CWI) on staff at the Ironworkers Local 512 Training Center. The typical certification test usually takes a minimum of 4 hours of welding to complete. All told, recertification might cost about $500 to the Ironworkers Training Center. If an Ironworker has to recertify in 2-3 processes, that cost adds up quickly! (We should note that there is no cost to the welder, other than their time and whatever it costs them to get to the Training Center.)

Far better (and less expensive) is just keeping the continuity log and welding skills up to date. If an Ironworker is getting to the end of their 6-month period, and they haven’t been welding, or haven’t been welding in one of the processes they’re certified on, the solution is simple and similar to recertifying: schedule a time to come to one of the Training Centers and weld in the process needed. This occurs under the direction and observation of the CWI on staff. The welder performs exercises to satisfy the AWS requirements, keeping the 6-month continuity window alive. When the process is complete, the CWI signs the welder’s continuity log, and they are good to go.

How Ironworkers Local 512 Does It

Each Ironworker who holds a welding certification is responsible for filling out their continuity log and getting it signed for each 6-month period prior to their expiration date. The easiest way is for the Ironworker to have their supervisor sign the log book and send Local 512 a picture of it. Ironworkers can also come into the Training Center, weld for the CWI, and then have the CWI sign their log book. It’s the welder’s responsibility to get a copy of the logs for the two 6-month periods preceding the expiration date to the Training Centers. Every week the Training Centers check the logs for accuracy and send them to the International Weld Control Program for final approval. The welder can expect a new welding certification card a few weeks after approval.

Nobody likes doing paperwork, but keeping continuity logs is important for keeping Ironworkers available for that part of the job. And technology makes this easier than ever. Set a reminder on your phone, recurring every six months, to make sure you get your continuity logs updated. It’s a good refresher if you haven’t been welding in one or more processes, and it’s required.

Ironworker Safety

“Work safe.”

It’s a phrase you hear all the time as an Ironworker. It’s a common way to end a conversation with another brother or sister Ironworker, whether in person or engaging online (r/Ironworker is peppered with it). It’s just two words, but it spotlights how important safety is for Ironworkers. For both the Ironworkers Union and the jobsite contractors, the order of importance is:

1. Safety

2. Quality

3. Production

It’s great when the work goes smoothly and structures go up fast. But injuries or rework can wipe out profit very quickly. Getting the job done safely and with high quality are the marks of skilled ironwork. Safety is always in the back of every Ironworker’s mind. There are simply no shortcuts to safety and quality.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

We’ve talked before about some of the general PPE Ironworkers use that are common to all the trades (safety glasses, ear plugs, hardhats, gloves, etc.). Ironworkers also wear sturdy work boots, though not typically safety-toed (what most people think of as “steel-toed boots”) unless the jobsite requires it. Also, good old blue jeans are the pants of choice, because the material holds up well around sparks. There is more PPE that is specific to ironwork but is also sometimes used by other trades. That includes things like:

· Welding gear—welding helmets or hoods, jackets, sleeves

· Fall protection—full body harness, anchorages, connectors

· Cutting torch safety—burning goggles

What We Protect Against

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has a category of construction industry hazards called the “Focus Four,” and Ironworkers are exposed to every one of them, no matter what facet of ironwork they are performing. The Focus Four are falls, struck by, caught in-between, and electrocution.

· Falls—this is the one that most people think of when they think about ironwork. And it makes sense: Ironworkers aren’t called “cowboys of the sky” for nothing. But there are so many, many more hazards on a job site that can bite an Ironworker if they are not in tune with their surroundings.

· Struck by—this includes things falling from above, such as loads from a crane or accidentally dropped tools, bolts, or any other object. But it also includes being struck by a vehicle, a real hazard when working on highway and bridge construction or repair.

· Caught in-between—this is exactly what it sounds like, and the most common caught in-between injuries come from swinging loads—like a steel beam being lowered into place or being caught between equipment and an immoveable object.

· Electrocution—this mostly refers to crane booms or aerial lifts contacting overhead power lines but can also come from using electric tools.

Safety Standards

Safety requirements on the jobsite are regulated by OSHA. Subpart R is the steel erection standard. The original standard from 1971 mainly had regulations involving rivets. The last big rivet job in Minnesota was in the early 70s. The standard was updated in 2001, and it changed how Ironworkers erect structural steel. There were major changes made in site layout, hoisting and rigging, structural steel assembly (including column anchorage, beam erection, and bar joist erection), falling object protection, and fall protection. There’s a saying that OSHA regulations are written in blood—that is to say, workers get hurt and then regulations are updated to prevent that accident from happening again—and many of the 2001 updates were in reaction to Ironworkers getting injured and killed on jobsites all over the country.

But making changes on paper is not the same as seeing them implemented on the jobsite. Ironworkers resisted the new safety requirements, arguing that the new regulations were not compatible with getting the work done efficiently. Well into the 2000s, Ironworkers hated to be tied off. They fought it until the alternative was getting fired. The general consensus was that it was impossible to be tied off and remain productive. In fact, some considered it to be more dangerous to be tied off. Especially among the Raising Gang, who are dealing not just with the height, the elements, and the narrow footing inherent in steel erection, but also massive steel beams being placed on the structure. Being agile and nimble is crucial in avoiding the Focus Four when erecting steel, and Ironworkers saw lanyards and tie-offs as something that interfered with their ability to move.

Over time, the safety industry innovated to meet efficiency, making being tied off easier and have less of an impact on mobility and productivity. These innovations include horizontal lifelines, retractable lanyards, and beamers (adjustable clamps that connect to wide flange beams but move with the Ironworker). Aerial lifts and work platforms are more common on the jobsite, too. All of this makes Ironworking much safer than it used to be—after all, prior to the 2001 revision, fall protection requirements were basically non-existent. The trade has gotten much safer than it used to be. Nevertheless, ironwork regularly makes the top ten in lists of “most dangerous jobs.”

Work Safe

Regardless of what part of the trade an Ironworker is performing, it is ingrained in every one of them that they are responsible for their own safety as well as that of the people they are working with every day. Ironworkers are taught to always know their surroundings—look at what is above you and what is below you. They always leave themselves an “out,” because if (and, in all likelihood, when) something goes sideways, it happens fast. The improved safety measures really have been effective: these days, an Ironworker who falls usually just takes a blow to their pride, rather than their body. And that’s why we are always there to remind each other to work safe.

We’ve written about mental health for Ironworkers in this space before. We’ve also touched on the fact that Ironworkers do hard work in tough conditions. There’s no question that the construction trades are hard work. It’s the type of work that can wear down a body. The everyday crouching, climbing, carrying, and clenching tools all take their toll. And Ironworkers use a lot of tools, but every Journeyman’s number one tool is their body. And that tool really gets put to hard use. Joints, especially, pay a price for the work. Many Ironworkers have had knees, hips, or shoulders replaced, and often at an earlier than normal age. Bad backs are a common problem, too. Ironworkers tend to do a lot of overhead work, and frequently have to work in awkward positions. Plus, there are environmental factors to consider. Working outdoors in the sun year after year is hard on the skin, and it creeps up on Ironworkers slowly. As a trade, we’re getting better about using sunscreen, but many Journeyman, especially older ones, never put it on.

Ironworking can be hard on hearing and sight, too. Construction sites are loud, making this is another area where damage adds up over time. There are a lot of older Ironworkers who wear hearing aids, and a lot more who probably should. Ironworkers who weld a lot can develop visual impairments beyond the typical ravages of time, and lung problems are not uncommon.

This all sounds pretty terrible, right? The good news is there are ways to mitigate the damage. Let’s look at some behaviors and resources that are available to Ironworkers to help heal and maintain their physical health.

First, general overall health is vital. Ironworkers look after and care for their personal tools; it’s important to apply the same level of concern to that number one tool by maintaining a healthy lifestyle. That means fueling your body properly, getting enough sleep, and staying at a healthy weight. It’s also very important to take advantage of the Ironworker’s Local 512’s great medical, dental, optical, and chiropractic insurance coverage. It covers all sorts of preventive services. Get those annual checkups and maintain your body!

Of course, this is a lot of the same advice that any doctor would give to anybody—not just an Ironworker. There are plenty of things that are specific to Ironworking that can help maintain your physical health. The first is always using the right personal protective equipment (PPE). Simply following best practices for using PPE can go a long way to keeping you healthy. This can be as simple as wearing ear plugs in loud environments. Hearing loss is a huge problem for Ironworkers. Younger Ironworkers often don’t wear ear plugs, and by the time they figure out they’re losing their hearing, it’s almost always too late: the damage has already been done. Another step is to always wear safety glasses. And when you’re doing a task that calls for custom PPE, such as welding, be sure to use the burning safety gear. Another sometimes overlooked part of keeping yourself healthy is wearing proper footwear. Supportive, protective work boots can help ease wear and tear on your feet and prevent injury.

Sometimes the PPE doesn’t even seem like PPE. For instance, one Ironworker had this story to tell:

When I was a young Ironworker, I used to jump off semi-trailers when we were done unloading them. A co-worker brought over a ladder for me to use to instead of jumping. He told me I would wear out my knees and hips hopping off the trailers. I didn’t listen, and 20 years later I was in for a hip replacement at 47 years old. I should have listened to him!

The Ironworkers benefit package includes access to an EAP—an employee assistance program. Our EAP is managed by TEAM, which works with labor and trade unions in the Midwest. TEAM helps our union members get help and care when they need it, whether for themselves or their families. They understand labor, how jobsites work, and what Ironworkers’ lives are like. They offer assistance for a wide range of things that can help improve the lives of Ironworkers and their families, from nutrition and wellness assistance to weight loss and quitting smoking to mental health and addiction; almost anything that can be a challenge in an Ironworker’s life, the EAP can help.

Ironworkers typically work hard and play hard (or harder!). It’s easy for physical health to take a back seat until you can’t grit your way through it, but that’s no way to keep your physical abilities for the long term, and that’s what being an Ironworker is all about: working hard, supporting your family, and retiring intact and with dignity. Physical health goes a long way toward making that retirement one you can enjoy to its fullest.

Cranes. They are ubiquitous on our jobsites. After all, it might actually be impossible, and certainly inefficient, to build high-rise towers, bridges, roads, or any large project without construction cranes. They’re the tool to raise or lower heavy materials, move them around the construction site, and keep the parts moving when constructing—or deconstructing—large buildings. Ironworkers use cranes every day for these purposes. Most of the time—like 99.9% of the time for Ironworker’s Local 512—the people operating the cranes are operating engineers who are members of International Union of Operating Engineers Local 49, known commonly as 49ers.

But for all the usefulness cranes provide, they also create additional jobsite risks. Among the most common dangers posed by a crane on a jobsite:

· The crane boom colliding with a building, another crane, or other object. This danger is mitigated by making sure the crane operator has clear visibility. If that visibility is compromised, there’s an Ironworker on the ground, known as a signal person, who communicates with the crane operator. They communicate using standard hand signals or voice signals as laid out in that OSHA 1926 Subpart CC and ASME B30. Voice signals are relayed via two-way radios when the signal person is not in clear view of the operator.

· Falling loads. Proper rigging is a vital part of crane safety. The 49ers and the Ironworkers know the load limits for the cranes, and know the weight of loads before they’re lifted. Ironworkers pride themselves on being the best riggers and signal people in the building trades. We use cranes every day to hoist our materials, and we are often hired to hoist materials for other jobsite trades as well.

· The crane striking an overhead power line. This is another area where the operator’s sight lines and working with the signal person are crucial. As with most of the dangers on any job site, maintaining power line safety is covered by OSHA rules (OSHA 1926.1408 Subpart CC).

· Tip-overs. Crane stability is key here, and getting the right setup can take a lot of preparation, beginning with assessing the ground conditions. Ironworkers are trained to know how and where to set up a crane, and what is necessary to maintain stability. You can see all of these risks reflected in these general rules of crane safety that we train all Ironworkers on:

1. Crane setup always follows the manufacturer specifications.

2. Always work within the limits of the crane’s load chart.

3. Never fly anything over the top of anyone. The riggers are the only exception here; they have to be beneath the crane’s load to hook and unhook it.

4. Keep away from powerlines, and always assume powerlines are live.

5. Know the weight of each pick and the capacity of the crane in the quadrant the crane is swinging through.

These are just some basic rules of safety in using a crane on a jobsite. We also train Ironworkers on things to do to keep themselves safe from cranes on the job site:

1. Never walk underneath a load hoisted by a crane.

2. Never enter the area inside the crane’s outriggers. The area should be should be marked by a warning line.

3. Always stay on the “safe” side of a crane load. This is the area between the load and the crane. Stay out of the “hospital” side of the load. This area is the area opposite the crane—cranes typically tip over forward, toward the load.

The 100% safe jobsite hasn’t been invented yet, and cranes bring another element of risk to our work. But part of being an Ironworker is having the knowledge and training to minimize risks, and making sure that everyone on the job knows how to perform it safely. If you’re interested in becoming an Ironworker, or learning more about being part of a raising gang, visit us at ironworkers512.com.

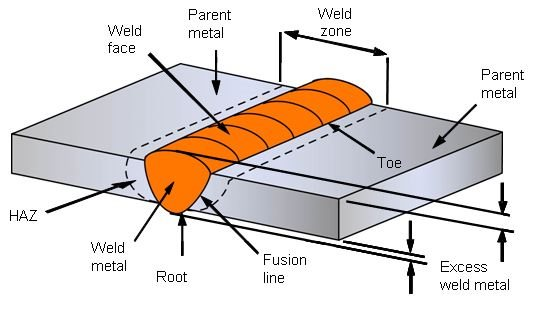

Welding is a core skill for an ironworker, a process that is necessary to join metals and fabricate our built environment and infrastructure. It’s a skill that takes time to learn and lots of experience to master. And even when it’s mastered, there’s the kind of mastery that makes itself visible in perfect conditions: a single waist-high weld, clear and easy access to the joint, on the ground, good weather, maybe even indoors. And then there’s the mastery that delivers quality welds in all the conditions that present themselves on job sites. Hundreds of feet in the air, in a confined space, brutal cold, having minimal access to the weld. The good news is that the Ironworkers Local 512’s apprenticeship program will teach you how to become a master welder, then give you the opportunity to hone those skills until you are one, under any conditions.

Types of welding

While many DIYers are familiar with welding, the type of welding they do is very different from what Ironworkers do. People welding in a shop or school are typically using a GMAW (Gas Metal Arc Welding) process. GMAW is a very user friendly, easy to learn method that you can quickly become proficient at. It uses a weld machine and feeder to deliver a solid or metal cored wire through a weld torch to the joint. The Gas part of GMAW refers to an inert shielding gas used to keep the atmosphere around the weld free from oxygen and nitrogen, two gases that are detrimental to weld quality.

Ironworkers, by contrast, primarily use SMAW (Shielded Metal Arc Welding) or “Stick welding,” as it’s called on the jobsite, and FCAW (Flux Cored Arc Welding), or, to the Ironworker, “Wire.” These processes are much harder to learn and master than GMAW due to the extra variables that come into play. One of the biggest differences in stick welding and wire welding is that they are “self-shielded” processes. No shielding gas is introduced into the process from an exterior source, as is the case with GMAW. That’s primarily because of the nature of Ironwork, which is that it’s mostly done outdoors, where any wind will simply blow away a shielding gas. The gas shielding for Stick/Wire welding comes from compounds in the electrodes themselves, which is why they are self-shielded. Self-shielded welding processes result in a heavy slag on the weld, a protective coating similar to glass that helps shape and cool the weld. Managing the slag, an other variables, is a skill that can take many months to learn and even many years to master.

Types of welds

There are lots of types of welds, but a few of the most common ones to the Ironworker are:

· Puddle weld

This is exactly what it sounds like: a little puddle of molten metal holding things together. Here is one holding down sheet steel decking used to cover a roof.

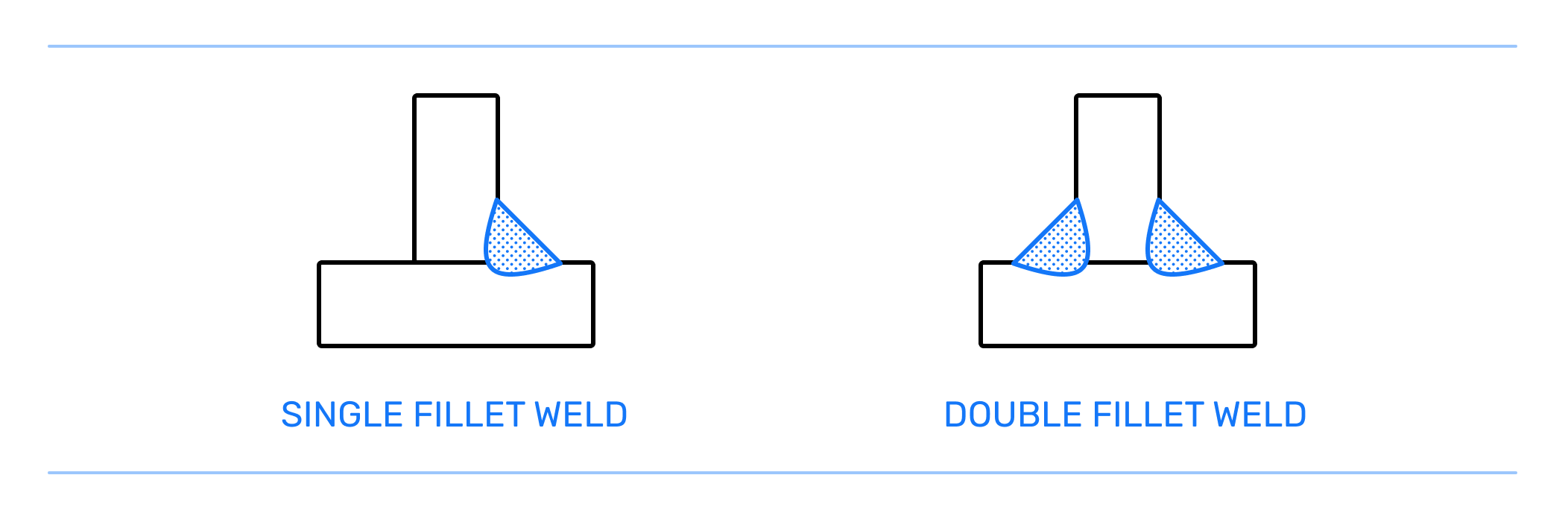

· Fillet weld

These are used in the corner made when two pieces of steel meet, like a T, and binds a vertical piece with a horizontal piece. They are the most common type of weld.

· Groove weld

These are the most complex and difficult of the three types listed here. Groove welds join two pieces of steel through their thickness. There are several types of groove welds that vary in difficulty and complexity, but the simplest type is a butt joint. Butting two pieces together and welding them together throughout their thickness.

Factors that affect Ironworkers’ welds

Beyond the welding process and the type of weld being used, there are many other factors that impact an Ironworker on a jobsite. Joint design, for example, affects weldability. If the design is wider and more open, that’s much easier to weld, but if the joint design is tight due to other constraints, weldability can get much harder. If it is a complete joint penetration with an open root, it will be much harder than if it is the same weld with a backer bar.

Accessibility is another factor. Where is the weld located physically? How easy is it to get to? Once you’re there, how easy is it to reach with the welder? Is the weld on the ground at chest level or is it, to pluck an example out of thin air, 127 feet above ground on the high bank of the roller coaster Wild Thing at Valley Fair, and the only way to reach it is to climb the track?

Obstructions are another major factor. Is there something in the way? Sometimes you have to contort yourself to reach the weld. Other times it’s completely obstructed and the only way to make the weldment is by using a mirror.

How the joint fits together is another factor. Sometimes the pieces of metal don’t line up like they are supposed to. This can pose a real challenge to a welder.

Visual appeal can sideline even the most experienced welders. Every Ironworker is going to do a good quality weld every time, but there’s less pressure to create a perfect-looking weld when you know it’s going to be hidden inside a wall, or buried underground. But if something is part of a show piece that will be highly visible, seen by the masses, then there’s an aesthetic component to consider as well.

These are just a few of the factors that Ironworkers deal with on a regular basis. There are many others, and every weld is different. Something that looks complex and difficult might turn out to be easy with a good plan in place. On the other hand, something that looks routine can become quite challenging when a few of these factors get mixed in. That’s actually one of the best things about Ironwork: every job is different and brings its own set of challenges.

Safety

Welding, with the ultra-bright flame, the heat, and the sparks, can look intimidating, even scary. But with proper training and personal protective equipment, it’s as safe as any other aspect of Ironworking, or the construction trades in general. The Ironworkers Local 512 is committed to safety, and our training is centered around recognizing hazards, preventing them, and making sure that Ironworkers follow the practices that keep them safe.

One last thing along these lines: don’t get sucked in by the welders who do their best work on YouTube instead of on metal. Most of them are self-proclaimed experts and some simply do not know what they are doing. Lots of them have bad habits, and if you don’t know how to spot them, you can pick them up yourself. With an audience always thirsty for a shortcut “tip” or “hack,” the YouTubers’ motivation is to give the audience what they want. And there is no hack to make you a better welder. There’s just training, practice, and discipline. In the end, the only hack is the person you’re watching on screen!

For more information about becoming an Ironworker, visit ironworkers512.com.

There are many paths that can lead a person to becoming an Ironworker. The brothers and sisters in Ironworkers Local #512 come from all walks of life. We have people with four-year degrees, high school dropouts, and everything in between and beyond. We even have a former medical doctor among our ranks. But regardless of race, age, gender, native language, or any other category that separates people, we are united by one thing: taking pride in doing hard work right.

Another thing that unites Ironworkers in Local 512 is our apprenticeship program. We mentioned above the many paths that can lead to Ironworking, but the apprenticeship program is how every one of us becomes an Ironworker. It’s the one door we all go through. But don’t think of it as restrictive. The apprenticeship program is, bar none, the best way to learn the trade of being an Ironworker. It’s also the least expensive. In fact, the “earn while you learn” part of our program is one of its main attractions.

First, a little bit about the apprenticeship program. It’s a four-year program, with two semesters each year. It does cost our apprentices—it’s $400 for each semester, for a total of $3,200 over the four years. That’s the total cost to you for tuition that trains you in every aspect of Ironworking. And while $400 can seem like a difficult sum, remember that this is for the “learn” part of the program. There’s also an “earn” part. While you are in the apprenticeship program, you’ll work on a jobsite with your crew, as well as other tradespeople. You don’t quite earn a journeyman’s wage, but you make 70% of it. In Region A, which covers roughly the southern half of Minnesota and a good portion of western Wisconsin, that’s $28.70 per hour in wages, plus a $33.39 per hour benefit package. Compare that to a four-year program at the University of Minnesota. You’re looking at roughly $18,000 per year in tuition (estimates vary, but that’s close enough) and maybe working part time for $15 an hour, no bennies. And when you’ve graduated, you have to find your own job.

That’s not to bash university education—different careers are great for different people. And apprenticing as an Ironworker isn’t easy. You work full days, full weeks, doing demanding work that can pose new challenges every day. And then you have to get yourself to class. The schedules run a little differently for each region, but in Region A that’s two-night classes per week, each two hours long, for sixteen weeks in the Fall and sixteen weeks in the Spring, including some Saturdays. It’s not easy! But you’ll be doing it with like-minded, determined people who lift each other up and have each other’s backs.

There are great benefits to becoming an Ironworker. You’ll be expertly trained in everything Ironworkers do, learning how to do it all safely and at high quality. You’ll make a great wage with great benefits, and lots of opportunities for success. As an Ironworker, you can go almost anywhere and make a living. This article from Forbes tells the story of Emily, a former #512 apprentice who’s now working in Los Angeles as a journeyman. This video tells Sovereign’s and Johanna’s stories. They’d had jobs in other fields but found them unsatisfying. They were looking for fulfilling, rewarding careers, and found them in Ironworking. Sovereign is now working in Milwaukee. They, like all Ironworkers, can be confident in knowing they’ll make a fair living during their careers and have a dignified retirement after their careers are over.

There are obstacles to becoming an Ironworker; the biggest one is probably that it’s hard work done in tough conditions, especially in this part of the country. Jobsites can be far from home, and you might not be able to return home every night during the work week. But for people who can envision themselves doing the work, it is a great opportunity. And it’s truly open to everyone: we’ve seen six-foot-four men popping with muscles who aren’t tough enough to do the work, while 110-pound women thrive.

If you think you have what it takes to be an Ironworker, find out how to get started in our apprenticeship program here.

Copyright © 2021 Ironworkerss Local 512. All Rights Reserved. Website designed and hosted by Esultants Web Services.